Shakespeare's sonnets: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (30 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Collection of 154 [[Sonnet|sonnets]] by [[William Shakespeare]] first published in 1609. The collection ends with the narrative poem "A Lover's Complaint". The first 17 sonnets of the collection are dealing with the topic of procreation and are addressed to a young man; sonnets 18-126 are dealing with the writer's love to the young man; the last sequence (sonnets 127-154) is dedicated to the Dark Lady. Due to its internal separation of addressees, the collection highly differs from other sonnet sequences making use of traditional Petrarchan features such as the sequences of [[Edmund Spenser]] and Sir [[Philip Sidney]]. | |||

Whereas the traditional concepts of Elizabethan (love) sonnets dealt with courtly love, Shakespeare changed some | |||

The sonnet collection also works through and with traditions and conventions. Whereas the traditional concepts of Elizabethan (love) sonnets dealt with courtly love in the manner of [[Petrarch]], Shakespeare changed some aspects such as addressing a young man and his beauty as well as contradicting the Petrarchan sonnet tradition with the sexually oriented sonnets about the Dark Lady. | |||

== Structure and style == | == Structure and style == | ||

Shakespeare makes use of Surrey's sonnet form with an abab cdcd efef gg rhyme scheme. Its metrical structure is iambic pentameter. | |||

The sonnets usually consist of two quatrains which emerge in a thematical octave, followed by a cesura in thought, a quatrain and a final rhyming couplet. Exceptions are sonnets 126 (which consists of rhyming couplets) and 145 (which makes use of 4 feet in one line instead of 5). The couplet is often set against the previous thoughts or else it is used for emphasis - it serves as a new form bringing reversal, new ideas or a conclusion (Schabert 653). | |||

Though the sonnet collection seems to follow a certain chronology, on closer consideration it is obvious that there are some irregularities. Thus, sonnets 76-86 deal with the poet's rival concerning the Fair Lord's love, but apparently sonnet 77 and sonnet 81 seem to be out of place. So, sonnet 81 offers itself to be a thematic and linguistic counterpart to sonnet 32 which itself functions as a thematically and linguistically foreign matter in its series of sonnets 29-35. According to that it is doubtful that Shakespeare's sonnets were written in the more or less precise order they appear in the collection. | |||

== Themes and motifs == | |||

Shakespeare uses metaphors, symbols and conceits (an extended metaphor, which gives the whole sonnet its content). In Renaissance poetry often hyperbolic comparisons to nature were made in order to admire the Sonnet Lady. Shakespeare repeatedly makes use of eye-conceits, which due to its ambiguity (homophone: eye - I) emphasise the importance of subjectivity and individuality. | |||

Due to its structure, one of the sonnet collection's main themes is the contrast between platonic love and carnal desire, between reason and lust. This is illustrated by the addressees, the Fair Lord, who stands for platonic love, and the Dark Lady, who is connected to carnal desire. | |||

One aspect recurs: the ravages of time. Specifically the decay and mortality of the human body and the immortality of the soul (and of art and writing) are central elements. Time is personified as the enemy which one cannot escape from, except letting the individual live on in descendants (as in the procreation sonnets) or being immortalised by art and poetry. | |||

== Sonnets 1-126: Fair Lord sequence == | == Sonnets 1-126: Fair Lord sequence == | ||

Sonnets 1-126 are addressed to an unnamed young man, occasionally referred to as “Fair Lord”. Here the speaker expresses his love and admiration for the Fair Lord, praising his beauty. The Fair Lord stands for an idealised platonic love. This varies the Petrarchan ideal since the speaker addresses a young man instead of the traditional unapproachable Sonnet Lady. This concurs with Neo-Platonic ideals, in which real love without sexual lust (as chastity is one of the ideals of the Petrarchan Sonnet Lady) is possible between men only. | |||

The Fair Lord, however, contradicts the Petrarchan ideal by being depicted as a human being. Though he is praised for his beauty, he is not wholly idealised by being criticised for being selfish and doing hurtful things to the poet (sonnet 94) such as having another friend – the Rival Poet who appears in sonnets 78-86. | |||

Sonnets 1-17 can be read as a micro-sequence, usually called “procreation sonnets”. A change in tone is given with sonnet 18, which combines the admonition to marry with the announcement that the poet's Fair Lord will be immortalised in his verses. It is a move to romantic intimacy, which continues in the following sonnets that depict the ups and downs of the relationship between the poet and the Fair Lord. They address the Fair Lord and try to persuade him to marry and start a family in order to save his beauty by means of an heir. Here, the sonnets are dominated by imagery of the world of finances and law, which ascribed the assumption that Shakespeare wrote the first sonnets on commission for a young aristocrat, whose family wanted him to marry. Aspirants for the position of the friend were [[Henry Wriothesley]], Earl of Southampton (to whom Shakespeare's Epics are dedicated) and [[William Herbert]], Earl of Pembroke (to whom the folio edition is dedicated). Both men were young when Shakespeare wrote the sonnets, and both could not decide to marry for a long time, so that they possibly required the admonitions of the procreation sonnets (Suerbaum 326). | |||

== Sonnets 127-154: Dark Lady sequence == | == Sonnets 127-154: Dark Lady sequence == | ||

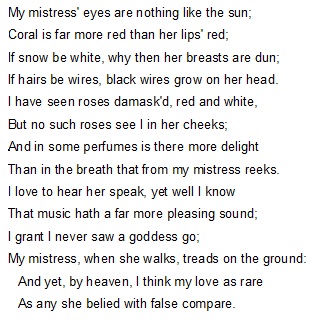

== | The topics of desire and physical attraction build the centre of the sonnets. Hence, carnal lust serves as an antithesis to the platonic ideal the speaker illustrated in the previous 126 poems. The style of the sonnets is Anti- (or Meta-)Petrarchan. Usually the admired Sonnet Lady stands for chastity, virtue, elusiveness and a set of standardised features (blond hair, blue eyes, pure skin), which turn her into a divine, angel-like creature. Instead, the Dark Lady is depicted differently in behaviour and appearance: | ||

[[File:Sonnet_130.jpg]] | |||

This sonnet is an example for a contre-blazon: Shakespeare mocks the traditional Petrarchan conceits, which idealise the Sonnet Lady and compare each of her body parts to beauties of nature. These typical idealisations are negated here – the Dark Lady is no goddess at all. The couplet makes clear that the poet does not need any false or exaggerated comparisons to distore his beloved's attractions since he is in love with a real woman. | |||

== Sources == | |||

Puschmann-Nalenz, Barbara. ''Loves of Comfort and Despair''. Frankfurt: Akademische Verlags-Gesellschaft, 1974. | |||

Schabert, Ina. ''Shakespeare-Handbuch''. 4th ed. Stuttgart: Kröner, 2000. | |||

Shakespeare, William. ''Shakespeare's Sonnets''. Ed. Katherina Duncan-Jones. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2007. | |||

Suerbaum, Ulrich. ''Der Shakespeare-Führer''. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2001. | |||

Latest revision as of 10:39, 10 January 2018

Collection of 154 sonnets by William Shakespeare first published in 1609. The collection ends with the narrative poem "A Lover's Complaint". The first 17 sonnets of the collection are dealing with the topic of procreation and are addressed to a young man; sonnets 18-126 are dealing with the writer's love to the young man; the last sequence (sonnets 127-154) is dedicated to the Dark Lady. Due to its internal separation of addressees, the collection highly differs from other sonnet sequences making use of traditional Petrarchan features such as the sequences of Edmund Spenser and Sir Philip Sidney.

The sonnet collection also works through and with traditions and conventions. Whereas the traditional concepts of Elizabethan (love) sonnets dealt with courtly love in the manner of Petrarch, Shakespeare changed some aspects such as addressing a young man and his beauty as well as contradicting the Petrarchan sonnet tradition with the sexually oriented sonnets about the Dark Lady.

Structure and style

Shakespeare makes use of Surrey's sonnet form with an abab cdcd efef gg rhyme scheme. Its metrical structure is iambic pentameter.

The sonnets usually consist of two quatrains which emerge in a thematical octave, followed by a cesura in thought, a quatrain and a final rhyming couplet. Exceptions are sonnets 126 (which consists of rhyming couplets) and 145 (which makes use of 4 feet in one line instead of 5). The couplet is often set against the previous thoughts or else it is used for emphasis - it serves as a new form bringing reversal, new ideas or a conclusion (Schabert 653).

Though the sonnet collection seems to follow a certain chronology, on closer consideration it is obvious that there are some irregularities. Thus, sonnets 76-86 deal with the poet's rival concerning the Fair Lord's love, but apparently sonnet 77 and sonnet 81 seem to be out of place. So, sonnet 81 offers itself to be a thematic and linguistic counterpart to sonnet 32 which itself functions as a thematically and linguistically foreign matter in its series of sonnets 29-35. According to that it is doubtful that Shakespeare's sonnets were written in the more or less precise order they appear in the collection.

Themes and motifs

Shakespeare uses metaphors, symbols and conceits (an extended metaphor, which gives the whole sonnet its content). In Renaissance poetry often hyperbolic comparisons to nature were made in order to admire the Sonnet Lady. Shakespeare repeatedly makes use of eye-conceits, which due to its ambiguity (homophone: eye - I) emphasise the importance of subjectivity and individuality.

Due to its structure, one of the sonnet collection's main themes is the contrast between platonic love and carnal desire, between reason and lust. This is illustrated by the addressees, the Fair Lord, who stands for platonic love, and the Dark Lady, who is connected to carnal desire.

One aspect recurs: the ravages of time. Specifically the decay and mortality of the human body and the immortality of the soul (and of art and writing) are central elements. Time is personified as the enemy which one cannot escape from, except letting the individual live on in descendants (as in the procreation sonnets) or being immortalised by art and poetry.

Sonnets 1-126: Fair Lord sequence

Sonnets 1-126 are addressed to an unnamed young man, occasionally referred to as “Fair Lord”. Here the speaker expresses his love and admiration for the Fair Lord, praising his beauty. The Fair Lord stands for an idealised platonic love. This varies the Petrarchan ideal since the speaker addresses a young man instead of the traditional unapproachable Sonnet Lady. This concurs with Neo-Platonic ideals, in which real love without sexual lust (as chastity is one of the ideals of the Petrarchan Sonnet Lady) is possible between men only.

The Fair Lord, however, contradicts the Petrarchan ideal by being depicted as a human being. Though he is praised for his beauty, he is not wholly idealised by being criticised for being selfish and doing hurtful things to the poet (sonnet 94) such as having another friend – the Rival Poet who appears in sonnets 78-86.

Sonnets 1-17 can be read as a micro-sequence, usually called “procreation sonnets”. A change in tone is given with sonnet 18, which combines the admonition to marry with the announcement that the poet's Fair Lord will be immortalised in his verses. It is a move to romantic intimacy, which continues in the following sonnets that depict the ups and downs of the relationship between the poet and the Fair Lord. They address the Fair Lord and try to persuade him to marry and start a family in order to save his beauty by means of an heir. Here, the sonnets are dominated by imagery of the world of finances and law, which ascribed the assumption that Shakespeare wrote the first sonnets on commission for a young aristocrat, whose family wanted him to marry. Aspirants for the position of the friend were Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton (to whom Shakespeare's Epics are dedicated) and William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke (to whom the folio edition is dedicated). Both men were young when Shakespeare wrote the sonnets, and both could not decide to marry for a long time, so that they possibly required the admonitions of the procreation sonnets (Suerbaum 326).

Sonnets 127-154: Dark Lady sequence

The topics of desire and physical attraction build the centre of the sonnets. Hence, carnal lust serves as an antithesis to the platonic ideal the speaker illustrated in the previous 126 poems. The style of the sonnets is Anti- (or Meta-)Petrarchan. Usually the admired Sonnet Lady stands for chastity, virtue, elusiveness and a set of standardised features (blond hair, blue eyes, pure skin), which turn her into a divine, angel-like creature. Instead, the Dark Lady is depicted differently in behaviour and appearance:

This sonnet is an example for a contre-blazon: Shakespeare mocks the traditional Petrarchan conceits, which idealise the Sonnet Lady and compare each of her body parts to beauties of nature. These typical idealisations are negated here – the Dark Lady is no goddess at all. The couplet makes clear that the poet does not need any false or exaggerated comparisons to distore his beloved's attractions since he is in love with a real woman.

Sources

Puschmann-Nalenz, Barbara. Loves of Comfort and Despair. Frankfurt: Akademische Verlags-Gesellschaft, 1974.

Schabert, Ina. Shakespeare-Handbuch. 4th ed. Stuttgart: Kröner, 2000.

Shakespeare, William. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Ed. Katherina Duncan-Jones. London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2007.

Suerbaum, Ulrich. Der Shakespeare-Führer. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2001.