Civil War

The English Civil War or the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (also called English Revolution or Great Rebellion) was a series of three connected civil wars, covering roughly the decade from 1642-1651. The two warring parties were Royalists (supporting King Charles I, and later his son Charles II) and Parliamentarians (fighting for a greater independence of parliament from the king, later for the abolition of the monarchy). The Civil War led to the execution of Charles I, the exile of Charles II and the foundation of the Commonwealth.

Background to the Civil War

Context

The early 17th century saw great social changes. For the first time, a literate lower middle class appeared, but also rich property owners, professionals and merchants became increasingly influential on an economic level, though politically the aristocracy and the King still concentrated more or less all power in their hands. However, King Charles I was widely seen as untrustworthy, stubborn and bad at communicating his ideas; his insecurities, paired with a strong understanding of Kingship (Divine Right of Kings) led him to the kind of arrogance ("Kings are not bound to give an account of their actions but to God alone".) that made his subjects see him as a potential tyrant.

Moreover, the kingdom was far from homogeneous. While, since 1603, England, Scotland and Ireland were ruled in personal union, the different countries showed deep religious divisions and very distinct cultures and institutions. Whereas his father, King James I, had a softer approach to merging his dominions, Charles I, in the eye of Barry Coward, hastened the process of union between England and Scotland.

The Religious differences were especially important. While Ireland was mainly Catholic, England's and Scotland's churches had undergone the reformation in very different ways. This and a number of puritan sects, for whom the Anglican church was still too Catholic, constituted an explosive religious situation.

On the Continent, the Thirty Year's War was raging since 1618, though mainly a conflict between the Houses of Habsburg and Bourbon, pitted Protestants against Catholics, with the latter seemingly getting the upper hand. This, combined with Charles' and his trusted Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud's moves to further embellish the Anglican church ceremonials led many to believe that Catholicism was on its way into Britain again. This fear was only exacerbated by Charles' decision to marry the Catholic Henrietta Maria of France against the will of parliament.

Events leading up to the war

Scottish Rebellion

In contrast to his father, who had been King of Scotland before being crowned King of England, Charles had lived in England since the age of 4. He therefore felt only little connection to Scotland and alienated the Scottish nobility by revocating some of their land titles. This, paired with extraordinary taxation, and a continously declining economy in Scotland led to open protest, which Charles answered by further weakening the political role of the nobility. Under this circumstances, Charles and William Laud moved to anglicanise the Scottish church. The introduction of a new Book of Common Prayer led to riots in Edinburgh. In the National Covenant the Scots rejected the changes introduced, which, after failed negotiations, led to open rebellion in 1639, then to two wars, which ended in a Scottish victory. Charles was forced to withdraw his changes and pay reparations to Scotland.

Short Parliament

In order to pay for the war, Charles had to call Parliament, which - instead of granting him the funds - began to discuss long-lasting problems and misgivings they had with royal policy. Especially John Pym was recognised as one of the major voices in this. Charles refused to discuss and dissolved parliament on 5 May 1640, not yet three weeks after the election.

Meanwhile, in Scotland, the Scottish Parliament, also decided on sweeping changes. In December 1639, parliament decided that from now on a dissolution would require the consent of the dissoluted parliament. In June 1640 they went even further, calling for more independence from London.

Long Parliament

Charles problems were not going away by themselves: Still broke, with the cost of both the war and the reparations mounting, and a partial tax-payers strike on his hands, Charles had to call in another parliament in November 1640. But in the few months since the dissolution of the Short Parliament, grievances had even increased. The main issues during the election were religion, that is the threat of Catholicism, and arbitrary taxation, both decidedly anti-royal topics. Accordingy, only 11% of the elected members of parliament were courtiers, officials or other close supporters of the king (Russell, 1990).

Thus, the issues that had not been resolved, but merely suppressed by the dissolution of parliament resurfaced again. John Pym and his supporters renewed their concerns over the King's policies and actions and with a parliament now decidedly sceptic of the King's behaviour Charles had to relinquish some of his powers in the course of 1641. Parliament had to convene at least once every three years and taxation without consent, as well as arrest without trial were outlawed. The kings administrative powers were weakened and parliament's grew in turn. Importantly, the persecution of dissenters also was stopped. Charles also agreed to an official day of fasting for the entire country on every last Wednesday of the month, something which would later prove an important outlet for radical puritan sermons against the King.

However, with the increasing radicalisation of parliament, the royalist party began to grow again. Many more modest reformers were alienated by the increasing radicalism, both political and religious. As property owners they were beginning to fear that law and order, and therefore the security of their property, would be threatened. Ever-increasing mobs in London, as well as riots and movements of non-rentpayers in the country, made them - though grudgingly - side with the King once again. While in May 1641 a mere 59 of 538 members voted against curtailing the kings powers, in June 1642 the royalist faction had grown to 236 members.

Many parliamentarians suspected the King, fearing for his power, to plan a military coup, especially after the unsuccessful attemt to arrest five leading opposition MPs (John Pym, John Hampden, Denzil Holles, Sir Arthur Haselrig and William Strode) on 4 January 1642. This in turn further radicalised parliament, now demanding control over the armed forces and the right to appoint government ministers. In March 1642 parliament decreed that its own Ordinances were valid by themselves, and did not require royal assent.

First Civil War (1642-1646)

Interestingly, though primarily a political conflict, the sides also were divided on religious grounds. According to figures from Russell, about 90% of the catholics sided with the royalists, while over 75% of the puritans became supporters of parliament. And even though their power was threatened as well well over a quarter of the nobility sided with parliaments.

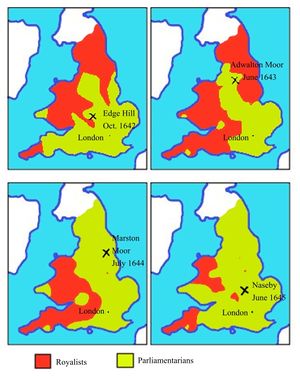

Parliament, now essentially independent of the King, split: Over 200 members left London for York, to where the King had retreated. With now only the anti-royalists present, a compromise was becoming ever more impossible. In the Summer of 1642 parliament set up a volunteer army to protect its new-won powers. The King also gathered his troops and on 23 October 1642 the First Civil War commenced with the Battle of Edgehill. While the war initially favoured the royalist, in autumn 1643 in the battles of Newbury and Winceby, the parliamentary forces got the upper hand. When in 1645 parliament reorganised its forces into the New Model Army, the war was already decided. The Battles of Naseby and Langport then effectively destroyed Charles' armies.

Second Civil War (1648-1649)

The second Civil War was more a series of royalist uprisings than a concerted war effort with a unifying strategy. Disbanded Royalist troops reformed, and in some cases unpaid Parliamentary troops defected to the Royalist side, but none of these proved much problems for parliamentary forces, who in all cases decidedly quelled the rebellions.

Both the leaders of the New Model Army and parliament tried to negotiate with King Charles I on ways to rule the country after the end of the war. However, after several failed attempts, many Army leaders were openly discussing how to establish a Republic culminating in a document called the Heads of Proposals. The Levellers manifesto Agreement of the People was one of the alternative proposals. In Pride's Purge, an army led by Thomas Pride seized control over parliament, and excluded all members who did not agree with the Army leaders. The much smaller parliament became known as Rump Parliament.

But the most important part of the Second Civil War was its aftermath. A large number of royalist prisoners were beheaded. The most prominent was, of course, on 30 January 1649, Charles I himself, having been tried for being a "tyrant, traitor, murderer and public enemy". Now without a king and ruled by parliament England had ceased to be a monarchy and became the Commonwealth of England.

Third Civil War (1649-1651)

Ireland had, since the Rebellion of 1641 mainly been self-ruled, as the King and then later Parliament, simply had more important issues to consider than to reconquer the neighbouring Island. However, with the final defeat of the royalists in the Second Civil War, Oliver Cromwell now led a campaign of the Parliamentary forces to reestablish English rule over Ireland. In a series of battles in 1649 and early 1650 he defeated the Irish forces. While a blow to Ireland, the consequent Acts of Parliament, especially the Act for the Settlement of Ireland 1652 and Act of Settlement 1662 were to become historically much more decisive.

In Scotland, Charles Tudor, the son of the beheaded Charles I who had struck a deal with the Scottish Covenanters, was declared King of Scotland. This was seen as a provocation by parliament, and in July 1650 Cromwell left Ireland to fight Charles in Scotland. The Siege of Edinburgh was unsuccessful and the parlamentarians had to retreat to Dunbar, where they defeated the Scots in September. In 1651 the New Model Army occupied most of Southern Scotland, but Charles, with another army moved into Northern England, where he gathered some new royalist support. However, after the decisive victory in the Second Civil War, just three years earlier, the number of royalists were much smaller than Charles had expected, so at the Battle of Worcester on the 3 September 1651, the Cromwellian Armies finally defeated the Royalists. Charles II managed to flee to France.

References

- Russell, Conrad. The Causes of the English Civil War. Oxford: OUP, 1990.

- Stone, Lawrence. The Causes of the English Revolution 1529-1642. London: Routledge, 1994.

- Ashton, Robert. The English Civil War. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1978.

- Carpenter, Stanled (ed). The English Civil War. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007.

- Carlton, Charles. The Experience of the British Civil Wars. London: Routledge, 1992.

- Coward, Barry. A companion to Stuart Britain. Oxford: Blackwell, 2003.